In this interview, Michael Lamb talks about The Arts of Leading: Perspectives from the Humanities and the Liberal Arts, exploring how the humanities offer essential insights into leadership. He argues that leadership is a liberal art, grounded in freedom, virtue, and human connection. Lamb highlights lessons from unsung leaders, the performing arts, and biblical figures like Moses, encouraging church leaders to center character, embrace humility, and lead with relational wisdom, courage, and hope in the face of change.

Jessica Anschutz: Michael, I want to invite you to introduce your book, The Arts of Leading: Perspectives from the Humanities and Liberal Arts.

Michael Lamb: This is really a book that tries to explore what we can learn about leadership from the arts and humanities. If you go to a bookstore and look at the shelf for leadership, you’ll often see books from business or from social science but not books from literature, history, or religion. What we argue is that those disciplines are really important for understanding leadership as a human phenomenon, not just as a management practice. Our real aim is to help readers and others think about leadership in its full complexity, which is often very relational and collaborative. Also to show the ways in which history, philosophy, religion, classics, music, theater, might uncover new ways of approaching leadership in ways that really help us expand our imaginations, and therefore, be more attuned to the ways in which leaders enact their own practices in the world in meaningful and effective ways.

Jessica Anschutz: Thank you, Michael. I really appreciate the central claim of your book that leadership is a liberal art. What do you mean by this?

Michael Lamb: When we hear about liberal arts, we often think about the ways in which a university might teach certain disciplines. But the actual root-word of “liberal arts” is “liber,” which in Latin means “free.” And so, “liberal arts” are those disciplines in ancient Greece and Rome that help their practitioners become free thinkers, to be virtuous citizens and good friends.

And so, we think the liberal arts are an important context for leadership, and that leadership itself, when understood properly, is a liberal art. It’s the art that helps us become free, both individually and as a community. And so, how to think about leadership in that context is really the aim of the book. It is to see leadership as a set of arts that can help us enact and pursue freedom in ways that are humane and virtuous. We think that reclaiming that view is very important, in part because so much of the work on leadership is done in a business or management context and includes nothing about the complex lessons of history or philosophy or religion that are so crucial to how we think about what human beings are and how human beings work together to achieve common goods.

And so, we think that the liberal arts are crucial to making sure we produce leaders who do care about freedom, and about virtue, and can resist instances of tyranny and domination that might exclude freedom or prevent others from working toward the common good.

Jessica Anschutz: One of the things I really appreciated about the book is that you have chapters from a wide variety of leaders in different fields, each of which has different leadership lessons that we can draw on from the liberal arts. I’m wondering if there may be one of those lessons that most surprised you, and if so, what is it and why?

Michael Lamb: There are so many surprises in this book. It began at a conference we held at Wake Forest with the Oxford Character Project back in 2019. At that point, we had the idea for the book, and we were really encouraged not only by how many people came to the conference but also how many new insights emerged over the course of that weekend. And so, I’ve been really surprised by the ways in which the visual and performing arts, especially, can really unlock new insights on leadership. We often think about leadership as a set of practices, but don’t think about the ways in which acting might help us think about how we show up and perform certain roles in the world. So, there’s a great chapter by Melissa Jones Briggs, who teaches at Stanford’s Business School, on how she uses acting techniques to help train future leaders to think about how they’re showing up and revealing their identity, or perhaps covering their identity, in ways that might make them safe for a certain kind of role. So, thinking about acting as a kind of technique was really surprising for me.

Likewise, there is a great chapter by Pegram Harrison, who teaches at Oxford’s Business School, about his own experience teaching leadership through conducting. He himself is a trained musician, but also a scholar of literature and the humanities, and he has this great workshop where he actually trains leaders by giving them a chance to lead a choir (probably a pretty common experience for many church leaders who listen to this podcast!). What he shows is that, if you ask someone who doesn’t know music to go conduct a choir, they’ll often start by raising their hands and trying to figure out what they’re doing. But that creates chaos, right? He says that often, the first thing leaders should do is ask what their choir needs. They never actually think to ask what they need; they just kind of assume they should start waving their hands and directing in some way. It shows the ways in which a common practice like conducting in the arts might help us sort of center, not the leader but those who are being led, in ways that makes their voices important to the process of achieving a common good. Those kind of insights about what we can learn when we sort of shift our perspective on leadership was really exciting for me and really opened my own views about how other forms of art, from poetry to painting and portraiture, might illuminate different aspects of leadership.

Jessica Anschutz: I think you’re right that there are many different lessons highlighted in the book, and I truly think there’s something for everyone in it. You’ve shared some about what has most surprised you. I’m curious now about what challenged you.

Michael Lamb: There are some really challenging chapters in this book, and I think what I really appreciated about them was the ways in which many chapters really elevate unsung leaders or lesser-known leaders as being crucial to what leadership is. For example, there are a few chapters on the Civil War as a context for leadership, and we might think about the Civil War as being this case of political leaders like Lincoln, for example, or military generals like Grant, who are making a difference. But what Thavolia Glymph shows is that we also can’t ignore the role of enslaved people and refugees in the war. What she does is a real deep dive into how these leaders, not often told as part of the history, were making real change in resisting injustice and helping to promote freedom.

By lifting up these unsung heroes, she shows how we should think about leadership and learning from history in a much more expansive way. These days, many people will do “staff rides,” as they’re called, of various battlefields. Glymph suggests we should do staff rides of different plantations to understand the ways in which people on those plantations were enacting resistance and helping to produce conditions for their own freedom.

I think it helps us not only think about the ways in which we understand what leadership is, but also how and to which history we look in order to understand our own roles as leaders and how we use that history to expand our leadership in productive and imaginative ways.

Jessica Anschutz: Thank you so much for highlighting the unsung leader’s aspect of the book. In chapter six, Marla Frederick writes about “women’s work” and the question of leadership. She says, “One cannot look for leadership only in the polished photos adoring the halls of our institutions. Leadership is about who gets the work done, advances the cause of the institution, and creates a vision for future generations.” How does her chapter help us think about the unsung leaders?

Michael Lamb: This is my favorite chapter in the book. Marla is the Dean of Harvard Divinity School, a great scholar of various traditions in the black church, and she’s done a lot of work on the ethnographies of various churches and communities. She writes a beautiful chapter about her own home church in Sumpter, South Carolina—First Baptist Missionary Church—which was founded three years after the Civil War in 1868 by those who were formerly enslaved. Historically, the record has been that it’s the celebrated men who founded the church. But when she dug into the archives to celebrate the church’s anniversary, she found a different story. It was actually three women: Tilda Bush, Minnie Blair, and Mary Mitchell, who organized the church. She really was surprised by this lesson, and how history often erases those who actually did the work of leadership.

Marla’s real goal in this chapter is to show the ways in which it’s those people doing work between Sundays—not just on Sunday morning—who are often the leaders of these communities. To show those who really see leadership, not as a matter of an individual’s charisma or power or office, but as trying to advance the common good and do the work, not just in a public way but often in very invisible ways, to serve other members of the church—for example, by helping their communities to deliver meals or take people to the doctor; and to serve them in ways that often aren’t seen but really make a difference when it comes to bringing the community together. And so, I think her chapter really gives us a sense of what it means to actually be a leader in ways that might not be as public but can be equally or even more powerful.

Jessica Anschutz: How might churches think about celebrating these unsung leaders?

Michael Lamb: Oh, that’s a great question. I think what Marla does in this chapter is really tell their story. And I think there are more occasions for us in our churches and communities to think about how we tell the story of these leaders by sharing their work in the sermons that we preach or in the awards that we might give to those in the church who are the critical leaders not often celebrated. One thing that we do in our own team at Wake Forest is we save a section of our team meetings to invite members to shout out others on our team have done really good work that week or that month. I think giving occasions for us to publicly acknowledge this work and its real impact helps us all remember the value of it and also makes others feel seen in that moment. So, the more that we can do as communities (be it in a church or a university) to elevate these invisible leaders and to acknowledge that the work they do is not just valuable but essential to the actual operation of that community. I think that’s what her chapter really does. It shows that it’s not just an additive kind of addition to the community. Actually, it’s the core of this work. The more we can recognize that the core is not just one person—not one charismatic leader, but a whole community of people—that kind of interdependence can help us overcome the kind of individuality that often attaches to the idea of leadership.

Jessica Anschutz: Those themes of community and relationship really are pulled through the book. I want to change our direction a little bit and look at chapter four, which is about Mosaic leadership. What are some of the leadership lessons highlighted there?

Michael Lamb: This is a great chapter by Alan Middleman, who’s a scholar of Jewish thought and has really studied Moses’ leadership for a long time. What Middleman shows is that there are many different ways that Moses is portrayed in the history of interpretation. Some by Martin Buber, as this worldly failure who really did not actually achieve his goals of carrying his people into the promised land but was led by divine calling that kind of transcended this world. Whereas somebody like Machiavelli sees Moses as this armed prophet who’s using force to really lead a people in a different way, often with violence as one part of that.

He offers a much less known view, which is from the rabbis in the Midrash, where Moses is portrayed as a different kind of leader. One who cares about being effective, not by exercising power in violent or vicious ways, but by really using persuasion. Not coercion. So, he’s engaged in exchanging reasons with those in his community and building authority by building trust. That is really built through his character, and as such, his own approach to seeking the common good, not just his own interest. It’s a much more expansive vision of leadership that really centers the importance of character and ensures the leaders aims are geared toward the community, not just their own interest. I think both Buber and Machiavelli missed that part of his leadership in how they portray him in these kinds of stark terms. It’s a much more mundane vision of leadership, Middleman argues, but often one that’s more relevant to us. Because we’re not—in our world—going to be armed profits (we hope), or worldly failures. We want to be effective in what we do, but that often means that we do it in ways that are less dramatic, but often quite impactful.

Jessica Anschutz: Michael, I know a lot of your work centers on leadership and character, so I want to build on your answer in thinking about this and ask you: How might churches do a better job of thinking about leadership and character?

Michael Lamb: That’s a great question. I think there are a lot of things that I’ve learned in my own experience at a university that’s helped me think about leadership in a different way. I think one is just centering character. In a leadership position it’s often easy to center either policy or structure as being what leaders do. They either occupy an office that has a role and a hierarchy of organization, or they make policies that shape the larger community. Those are really important functions of leadership. But what those often do is really stress the institutional part of leadership, not the personal part and the human part. I think leadership is fundamentally relational. Without people who might follow us, there can be no leaders. So, leaders are really someone who build relationships, and often we see that the most important relationships are those that are built on trust, and that trust really depends on character.

Really, it’s centering these key virtues that are important for the church. Things like compassion—imagining someone who might be struggling—and how you might show compassion to them. It is having the humility to recognize our own limits and the planks in our own eyes before we start criticizing others or being encouraged to voice views and perspectives that might challenge the status quo but that also invite people into a conversation that really helps to imagine a wider community. Thinking about those virtues is important for us.

Now, they’re part of the tradition of Christianity in a very central way, but often we see them more as content for a sermon than a way of imagining our way of being in the world. The more we can embody those examples—and therefore be an exemplar for others in our community while also recognizing that we also are imperfect—that we’re not a fully formed person yet and that we’re on our own journey. That kind of humility invites them into a shared journey toward a common goal, not just as one person above them leading them in a certain direction. So, I think the more we can think about character as part of leadership, the more we’ll be able to center those relationships that are crucial for building authority but also helping build trust.

Jessica Anschutz: Thank you so much, Michael, for emphasizing that it’s an ongoing work for all of us and takes effort and intentionality as we strive to lead. I’ve got two more questions for you. What words of advice do you have for church leaders who are leading change?

Michael Lamb: Change is hard. Change can be very difficult for both leaders and the congregations. Again, I think the virtues are really important here. First, I think it is important to have a clear sense of purpose: Why are we changing? Change on its own is not enough. We need to know why we’re changing. Is it to create a more loving or just community? Is it to help to be more inclusive? Is it to be more expansive in our vision? Being very clear about our purpose, our “why,” and making sure we articulate that in ways that people understand is really important for us.

Second, having humility and recognizing that, as Pegram Harrison said, “It is not just a conductor who’s actually leading; actually, it’s the people in the choir too, who need to give us their voices.” So, having the humility to listen and to invite perspectives and input. The more that we actually are inviting people into the conversation and empowering them to lead with you, I think the more effective your leadership will actually be.

Third, having empathy for people who might have different perspectives on change, and finding ways to understand their perspectives and make sure they feel seen, if not always agreed with. That’s going to be important for maintaining unity in the midst of change.

Then, courage is a crucial virtue. Anytime that change is happening, it takes a lot of courage. There will be obstacles to it. There will be people who challenge such change. So, knowing your “why” and knowing your purpose can give you resilience and courage in the face of those challenges because you actually know you’re doing it for a good reason. If you begin to second guess yourself then that becomes really difficult. But, if you also lack humility to actually question your own views, then you might lead people in the wrong direction or perhaps leave people behind who might otherwise come with you. Those key virtues are really invaluable for navigating change in our current moment.

Jessica Anschutz: Thank you so much, Michael. It’s been a joy to talk with you today. As we wrap up, I want to ask: what is your hope for church leaders?

Michael Lamb: Thank you, Jessica. I think a lot about hope. I’ve written a whole book on hope and the work of St. Augustine, and I think my hope is that church leaders really see themselves as people who not only profess a certain vocation or tradition but also try to practice and live it. We can make sure that our professions—be that as teachers in the classroom or as preachers in the pulpit—embody our deepest values not just in superficial ways, but in real ways that are often unseen. Then, we can invite others in our lives to hold us accountable to that. You know, it’s my best friends who become great accountability partners for me and help me sort of recognize when I’m falling short of my aspirations but also help give me guidance and support when I need a boost. Finding those relationships among people, both within our churches but also beyond our churches, can be invaluable for us as we really advance the change that the world needs.

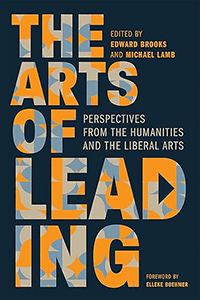

The Arts of Leading: Perspectives from the Humanities and Liberal Arts (Georgetown University Press, 2024), edited by Edward Brooks and Michael Lamb, is available from the publisher and Amazon.

The Arts of Leading: Perspectives from the Humanities and Liberal Arts (Georgetown University Press, 2024), edited by Edward Brooks and Michael Lamb, is available from the publisher and Amazon.

Related Resources

- Change Leaders Persevere by Ken Owens

- 7 Characteristics of Humble, Confident Leaders by Kay Kotan and Phil Schroeder

-

Moses, Pyramids and Leadership After Empire featuring Kathleen McShane and Elan Babchuck — Watch the Leading Ideas Talks podcast video | Listen to the podcast audio version | Read the in-depth interview

If you would like to share this article in your newsletter or other publication, please review our reprint guidelines.