Leaders create holding environments for innovation in part by helping the community interpret its legacy, present situation, and future. This centers on asking questions to which leaders genuinely do not know the answer, questions for which there are no easy answers, questions that the community must own and engage. Organizational scholar Edgar Schein calls this “humble inquiry” — the art of drawing people out, building relationships based on curiosity and interest, and recognizing that we need each other’s expertise in order to move into the future.

Church leaders are curators and stewards of the stories and practices of the community, which means they must help the church identify a useable past. Again and again in the biblical story, leaders help people connect their present situation with God’s faithfulness and promises. In the Hebrew Bible, the simple formulation “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” evoked stories of God’s blessing, call, and accompaniment of ancestors through difficult circumstances. The prophets tell and retell the story of God’s steadfast loving kindness, often in relation to an ambiguous present. Jesus situates his own ministry within this rich history, reading from Isaiah 61 in his hometown synagogue and evoking a powerful message of liberation and redemption. Peter, Paul, and the early apostles preach about Jesus by retelling Israel’s own story.

What Jesus did was to change people’s expectations so that they could see, interpret, and experience the world differently.

Where does a useable past lie in your church’s history? I once had an opportunity to speak with a large group of Lutheran pastors in a rural Midwestern area where the population has been draining away for years as farms become larger and more mechanized. Their towns and churches are in decline. Moreover, the new neighbors who have arrived speak Spanish, Hmong, or other unfamiliar languages to these descendants of nineteenth-century Norwegian, Swedish, and German immigrants. Amidst the deterioration of a treasured and established way of life, it would be easy to succumb to despair.

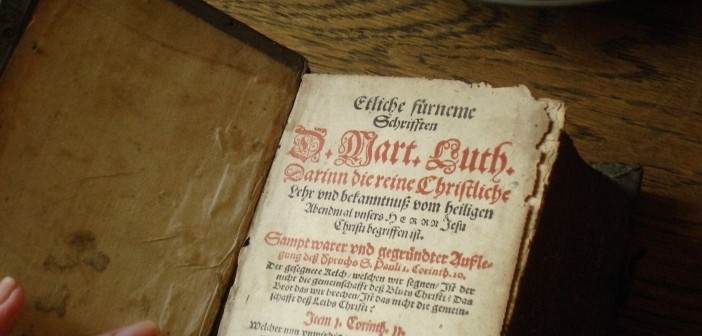

But deep in their heritage is a pioneering legacy — the legacy of resilient nomads who came to this land seeking opportunity and started new churches under difficult circumstances. What might it mean for them to be pioneers today in a culture that no longer supports Christian practice? If their identity is in part being a church of immigrants, can they become churches for their new immigrant neighbors? One leader found an old sign in the basement of his church that read, “Norwegian service upstairs, English service downstairs.” He hung this sign back up as a way of inviting his congregation into a different imagination about its identity. It changed the conversation about holding a Spanish service in this church, because people began to link their new reality with a bilingual landscape they had inhabited before.

This work of reframing the story in which people experience their world is vital for innovation, learning, and change. Scott Cormode explains that everyone operates with expectations that shape what they see. Culture provides a repertoire of meanings that we use to make sense out of a situation facing us. What Jesus did was to change people’s expectations so that they could see, interpret, and experience the world differently. In today’s secularized culture, many church members operate with secular expectations and cultural meanings as they make sense out of their lives. This leads to profound reductions of Christianity like Moralistic Therapeutic Deism or ethical spirituality in which people interpret their experience out of contemporary secular culture’s largely impoverished resources.

The renewal of mind to which the gospel invites us involves drawing from a different repertoire of cultural resources that can be woven into a narrative structure and lead to action. It means inhabiting a story in which our identities are a gift, not a project of our own construction, a story in which the liberating God of the Bible is up to something in our midst today, a story in which the Spirit of God is continually bringing forth new life, even out of death. It draws us deeper into the tradition and its rich stories and practices, deeper into our histories, and deeper into relationship with our neighbors in a posture of humble inquiry.

This article is excerpted from Dwight’s book, The Agile Church © 2014 Church Publishing Inc, New York, NY 10016, and used with the publisher’s permission. It is also available through Cokesbury and Amazon.

Related Resources:

- Continuity and Change: Two Tunes All Leaders Must Know by Lovett H. Weems, Jr.

- Your Church’s Creation Story by Tom Berlin

- Getting Your Congregation’s Story Right by Gil Rendle