Presenter

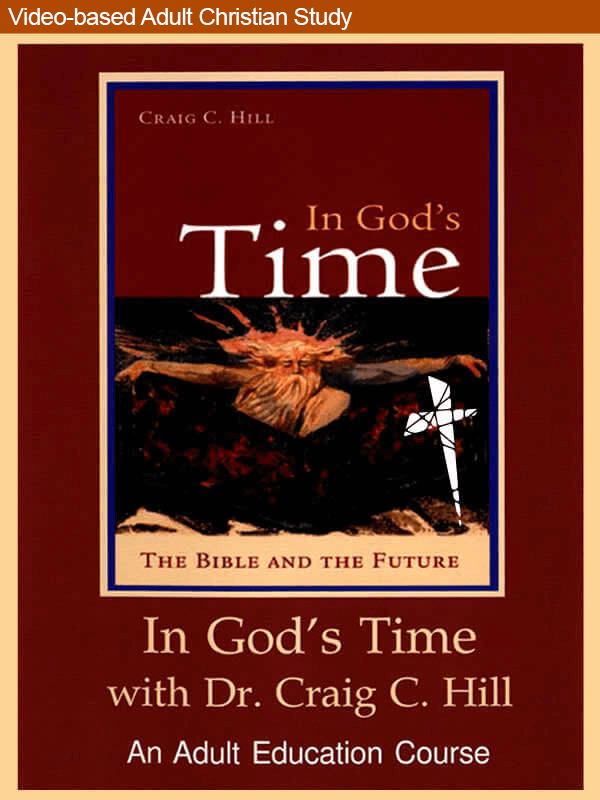

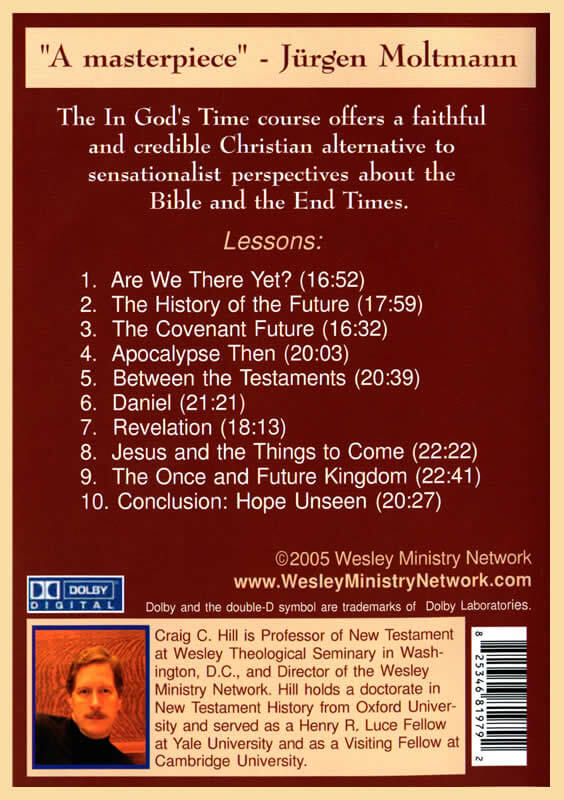

Dr. Craig C. Hill is dean of Perkins School of Theology in Dallas. A New Testament scholar, Dean Hill previously served on the faculty of Duke Divinity School, where he was executive director of the Doctor of Ministry and Master of Christian Practice programs. He also was a research professor of theological pedagogy. Prior to his tenure at Duke, he held numerous positions over the course of 15 years at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. They included professor of New Testament, executive director of academic outreach, director of the Wesley Ministry Network, co-director of the dual degree program with The American University and director of the Master of Theological Studies degree program. Education: D.Phil. University of Oxford; M.Div. Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary; and B.A. Illinois Wesleyan University. Selected publications include Servant of All: Status, Ambition, and the Way of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Press, 2016) and In God’s Time: The Bible and the Future (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Press, 2002).

Dr. Craig C. Hill is dean of Perkins School of Theology in Dallas. A New Testament scholar, Dean Hill previously served on the faculty of Duke Divinity School, where he was executive director of the Doctor of Ministry and Master of Christian Practice programs. He also was a research professor of theological pedagogy. Prior to his tenure at Duke, he held numerous positions over the course of 15 years at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. They included professor of New Testament, executive director of academic outreach, director of the Wesley Ministry Network, co-director of the dual degree program with The American University and director of the Master of Theological Studies degree program. Education: D.Phil. University of Oxford; M.Div. Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary; and B.A. Illinois Wesleyan University. Selected publications include Servant of All: Status, Ambition, and the Way of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Press, 2016) and In God’s Time: The Bible and the Future (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Press, 2002).

Sessions and Video Presentations

- Are We There Yet? (16:52)

- The History of the Future (17:59)

- The Covenant Future (16:32)

- Apocalypse Then (20:03)

- Between the Testaments (20:39)

- Daniel (21:21)

- Revelation (18:13)

- Jesus and the Things to Come (22:22)

- The Once and Future Kingdom (22:41)

- Conclusion: Hope Unseen (20:27)

Session 1 Video Preview

Session 1 Sample from the Participant’s Guide

Click to view a PDF of Session 1 materials from the Participant’s Guide.

Study Includes

- 10 lessons on download or DVD

- Leader’s Guide (spiral-bound or PDF version)

- Participant’s Guide (PDF)

- Weekly letter from Dr. Hill (PDF)

The In God’s Time book (available at Amazon) is an optional but helpful addition to the course.

- Instructional Segments

- Session 1. Introduction: Are We There Yet? (16:52)

This session focuses on the meaning and importance of eschatology. It challenges both an uncritical embrace of eschatology on the part of some Christians and an overhasty divorce from it on the part of others. It also highlights problems with traditional eschatologies, such as their view of time, cosmology, and creation. Modern Christians must face these issues squarely as they think about this vital subject.

Session 2. The History of the Future (17:59)

Many of the biblical writings deal in some way with the future. Naturally, this is true of the prophetic books. It was common in the ancient world to believe that the future could be predicted. However, it was seldom easy to tell which prophets were true and which were false, an issue that the biblical writers take up at numerous points and in various ways.

Session 3. The Covenant Future (16:32)

Increasingly, the prophets also foretold a renewed world in which God’s righteousness would reign over all people. In this and other ways, they thought from the perspective of faith about the future. In the work of the later prophets of the Hebrew Bible, we witness the beginnings of apocalyptic thought. A future is imagined that could be brought about only by an extraordinary act of God.

4. Apocalypse Then (20:03)

Apocalyptic thinking flourished in times of turmoil and dislocation. Such thinking was widespread in the Judaism of the inter-testamental period (that is, in the centuries between the Old and New Testaments). Apocalyptic texts wrestle with the problem of evil. They assert that “despite all appearances to the contrary, God has everything under control,” and believers are exhorted to endure persecution. A number of the ideas and images common to Jewish and Christian apocalyptic writing were also found in surrounding cultures.

5. Between the Testaments (20:39)

1 Enoch contains the earliest and most important of the non-biblical apocalypses. Many parallels exist between the New Testament and 1 Enoch. Seven key predictions common to apocalyptic literature are listed with examples taken from a range of ancient non-biblical works. Each of these points has some counterpart in the New Testament.

6. Daniel (21:21)

Daniel and Revelation tend to be regarded either as books of historical foresight or theological insight. The figure of Daniel appears prior to the setting of the biblical book of Daniel. The narratives of Dan. 1-6 are different in many respects from the apocalyptic materials found in chapters 7-12. The visions of Daniel center on the figure of the Antiochus IV, who prohibited Jewish practice and desecrated the Jewish temple. The author(s) of Daniel anticipated a soon-coming vindication of Israel and the resurrection of the most righteous and the most wicked.

7. Revelation (18:13)

The situation in which Revelation was composed is similar in many respects to that of the book of Daniel. The author of Revelation made extensive use of Daniel and other apocalyptically-oriented biblical writings. Much of Revelation is taken up with descriptions of the judgments awaiting God’s enemies, in particular, the emperor, the imperial cult, and the city of Rome itself. Revelation ends with a glorious vision of “the world reborn and Paradise revisited.” Revelation does not provide us with a “roadmap” to the future; nevertheless, it is a valuable book that still challenges and inspires modern believers.

8. Jesus and the Things to Come (22:22)

Two key questions in New Testament study are: Was Jesus an eschatological figure? And, did the early Christians, including the New Testament authors, basically get Jesus right? Christianity arose astonishingly quickly and spread rapidly. These facts weigh against the notion that the early church fundamentally misunderstood and/or misrepresented Jesus. Jesus proclaimed the dominion of God, which was both present and future and which was characterized by reversal. Jesus’ teaching also included mention of a future judgment. Jesus believed that he himself would play a central role in the realization of God’s reign.

9. The Once and Future Kingdom (22:41)

The crucifixion and the resurrection of Jesus were regarded as eschatological work already done. The early church’s eschatology

shifted over time, for example, from a more “future” to a more “realized” eschatological perspective (i.e., toward an increasing emphasis on the things that Jesus had already accomplished). The distinction is evident

in the New Testament as well as in contemporary Christianity. The eschatology of the apostle Paul makes for an especially interesting study. Two patterns of theological orientation correspond to future and realized eschatological perspectives.

10. Conclusion: Hope Unseen (20:27)

Today’s most popular form of eschatology, Premillennial Dispensationlism, goes back to the 1820’s and 30’s. Its founder, John Nelson Darby, argued that Christ would return twice. His interpretation of Scripture is ingenious, but it flies in the face of the biblical witness. It borrows widely from a range biblical authors and creates a single eschatology that is actually foreign to all of them. Hope is not the same thing as certainty. There is much we do not know about the future, but we may trust the future with God. Christianity is a religion of hope. To live Christianly is to experience newness of life now.

Audience

In God’s Time is appropriate for laypersons in churches of all denominations.

Schedule

The course schedule is set by your local church. Like other Lewis Center studies, you may begin and end the class based on your church’s own calendar

Online Small Groups

To help congregations that might be unfamiliar with the technical aspects of distance learning, we have assembled a How-To Guide For Online Studies webpage filled with helpful tips and suggestions to get your study groups online.

Free Publicity Materials Downloads

About the Download Files

Each video and PDF will be available for download individually. All the files together are 1.4 GB, so you may wish to save everything to a flash drive.

Upon purchase, you will receive an email that includes your receipt and download links. Please save this email for future use if you do not download all the files at once. If you do not receive this email, please check your spam or junk mail folder and search for wesleyseminary.edu. All files will be available for download for one year from date of purchase.

Usage Rights

In God’s Time is designed for use within a single congregation or charge. To purchase rights for further distribution, please contact the Lewis Center at (202) 664-5700 or lewiscenter@wesleyseminary.edu. Bulk rates are available.